|

James Graham: The Marquis of

Montrose (1612 – 1650)

James Graham, Marquis of

Montrose was born in 1612 and succeeded his father in 1627. He was among

the first to sign the National Covenant in Greyfriars Kirk in 1638 and

was, for a while, a most diligent servant of the Covenanters. He was

ignored for service by King Charles but, like so many other Scottish

Lords, he disapproved of the power that had been given to the bishops. As

one of the older noble families, his estates at Braco had been carved from

the bishopric of Dunblane and he would have been concerned if there was a

move to reclaim Church lands by the new order.

Nonetheless, he sat in the

first General Assembly at Glasgow as an Elder and was soon despatched in

July 1639 to bring the people of Aberdeen to heel. In this expedition he

was accompanied by another great general, a former field marshal in the

Swedish Army, Alexander Leslie. Unsuccessful with persuasion, Montrose was

to return after outbreak of the First Bishops War and quickly subdue

Aberdeen by force.

By 1640, between the

Bishops Wars, Montrose was beginning to

think that the Covenanting revolt had gone far enough and was beset by

problems of conscience over the National Covenant’s requirement of defence

of both Kirk and King. Concerned also

at Argyll’s rampaging and self-interest, he sought out others of like

conservative mind to form the “Cumbernauld Bond”. But this did not stop

him from leading the Covenanting Army into England, crossing the Tweed in

August, 1640, and trouncing the Royalist army at Newburn on August 28, as

well as entering the city of Newcastle on the 30th.

In the ensuing peace after

the Treaty of Ripon, he corresponded privately with Charles but all it got

him was a rebuff and the summer of 1641 locked in Edinburgh Castle when

the Covenanter leaders, especially Argyll, learned of his contact with the

King. In the aftermath of the Bishops Wars and further falling out amongst

the Covenanters, Charles threatened to bring in support from Ireland. This

threat was of considerable concern to Argyll, whose Clan Campbell had long

been at odds with the MacDonalds in the West.

But it was not until 1644 that it came to

reality. The Scottish politicians blundered badly when they hoped that

Montrose would lead their army against the Irish. But Montrose had only

objected to the Earl of Antrim leading them; he did not object to service

of the King nor to the use of Irish soldiers in Scotland.

So it was that he changed

sides and began a year of startling and often brilliant battles against

the Covenanter Armies, and humiliation for the Marquis of Argyll.

Montrose wished to act with the full authority of the King but this

arrived almost three months too late for him to join in an uprising by Sir

John Gordon of Haddo. This rebellion failed and Haddo and supporters

became the first casulaties of systematic execution.

In April, 1644, Montrose

had taken 1000 men with him and seized

Dumfries – but had no local support. Meanwhile the Marquis of Huntly had

similarly seized Aberdeen for the King. But in

the face of the local indifference, Huntly disbanded and retired to his

castle while Montrose pondered the next step – when and if the troops from

Ireland arrived. In Ireland the Earl of

Antrim’s army was also delayed waiting for weapons and ammunition to be

delivered, but it headed out from Fort of Passage, Waterford, on June 27,

1644. On their way across the Irish Sea the frigate “Harp” carrying

Alastair McColl or MacDonald, and his officers came across three vessels,

two with food and much needed provisions and the third carrying some 40

covenanters including 3 ministers – Rev Weir, Watson and Hamilton who were

taken hostage.

The force landed at

Ardmurchan on July 8, 1644, and found that the promised help of the Earl

of Seaforth had evaporated – he had joined the Covenanters. However, the

two Argyll forts of Mingarrie in Ardmurchan and Lochaline in Morven were

poorly guarded and quickly seized. These were to be important staging

posts for the Irish forces in the months ahead.

MacColl then unleashed his ferocious band of

about 1200 seasoned soldiers on northern Argyllshire and the Seaforth

lands punishing the Clan Mackenzie. Arriving at Badenoch he sent a fiery

cross to the Covenanters of Moray commanding them to rise and follow

Montrose. History is unclear

which band saved which but Montrose, learning of MacDonald’s arrival in

Badenoch, moved out to meet him at Blair Athol leaving the Irishmen to

fight their way there. This they did, even though outnumbered and pursued

by Argyll with three times the men, they had stormed the castle at Blair

Athol before Montrose got there.

Tippermuir: September 1,

1644

Needing provisions, the

combined force of hardened military Irishmen and Montrose’s local recruits

turned to attack St. Johnstone (Perth).

Arriving on the plain of Tippermuir they were confronted by the Covenanter

“Army of God” of 8000 men, led by David Wemyss, Lord Elcho. Armed with nine cannon and a detachment of

cavalry numbering 800 the Covenanters were the stronger party, on paper. Montrose placed

MacColl and his band at the centre, his bowmen under Lord Kilpont to the

left and Montrose and his Athol men to the right. The royalist victory lay

in the daredevil charge of the Irish who, having only one round for their

muskets, dashed in close, fired their one shot, then reversed their

weapons and used them as clubs – an unknown tactic in those days.

Then, having gained a foothold, the Irishmen

resorted to using the skein or short sword with which they were so adept.

The Covenanter cry of “Jesus, and no quarter” was of little use to them as

they broke ranks and fled, with over 1300 of them dead on the battle

field. and 800 taken prisoner.

After two days of plundering Perth the

little army of Montrose crossed the River Dee at Crathes, about 15 miles

north of Aberdeen and marched on the city. On September 13, 1644, they

found about 3000 foot soldiers, 500 cavalry and 3 cannon facing them.

Here, too, the Irishmen seemed to be at the

heart of things with Captain John Mortimer adopting another unusual

stratagem of mixing foot soldiers within the cavalry and adopting the wild

charge upon the Covenanters. Captain

Mortimer would later follow Montrose into exile and return in 1650 to

fight at Philiphaugh. Elsewhere, Sir William Forbes of Craigievar charged

his cavalry at Alexander McColl’s troops who fell apart and let them

through, then turned in on them and slaughtered the rest. The Covenanters

lost about 800 killed.

After Aberdeen, the victors

returned to Blair Athol where a detachment

was sent to the assistance of the Irishmen left at Mingarrie and Lochaline

who were under attack from Argyll. On

the face of it Argyll was seeking to save the three Covenanter ministers

who had been captured and which would have been readily exchanged for

Alexander McColl’s father and two brothers whom Argyll held captive. He

refused to exchange and pursued his attack as the castles were critical to

the defence of his lands. But when the relieving Irish troops came near,

the assault was abandoned. Arising from

this failed siege was the joining of the Clanranald of Lochaber, including

all the MacDonnells of Garragach and Keppoch, and the MacDonnells of

Glencoe, to the Royalist cause.

Fivy, October 28, 1644

Meanwhile Montrose’s

campaign restarted by marching from Blair Athol towards the lowlands when

the armies came across one another at Fivy, west of Montrose, on October

28, 1644.

Argyll and his troops had

been tracking the movement of Montrose’s forces at a respectful distance

and had occupied themselves by devastating the districts of Lude, Speirglass,

Fascally, Don-a Vourd and Ballyheukane, firing the land to Angus and

northwards to Dunnottar. His force of

1000 claymores, 1500 militiamen and seven troops of cavalry under the Earl

of Lothian came upon Montrose and his troops. Once again it was the

Irishmen, this time under Captain Manus O’Cahan who dislodged Argyll’s

troops from an important firing position. The Covenanters again turned and

fled with many of the cavalry especially, left dead.

Campbell lands –

Inveraray December 1644 – January 1645

Montrose returned to Blair

Athol to be rejoined by Alexander McColl who had been on a recruitment

drive in the northwest. With him were John of Moydart, Captain of

Clanranald and 500 men; Keppoch and his men from Lochaber; the Stewarts of

Appin, the warriors of Knoidart, Glengarry, Glennenis and Glencoe;

Camerons from Lochy and Farquharsons of Braemar. These had all suffered

under Argyll’s fire and sword attacks and it was resolved that they should

similarly retaliate. Now in the depths of winter Argyll had returned home confident that he was safe in his remote estates. But Montrose and MacColl refused to accept the difficulties inherent in winter campaigning, and decided to attack the Campbell lands. The Montrose forces were thus divided into three

divisions, one under Montrose, a second led by Alexander McColl and the

third under John of Moydart.

They descended on the

Campbell lands between December 13, 1644, and January 29, 1645, burning

homes and raiding for cattle throughout in Glenurchy, Inverawe, Lawers in

Breadelbane and then to

Auchenbrach in Kintyre. They left 900 Campbell soldiers dead in their

wake. The Marquis of Argyll had been

at Inveraray on the shores of Loch Fyne and when he heard that Montrose

was actually coming through the Highlands he fled, taking a fishing boat

on the loch and to all intents and purposes abandoning his people.

Tales vary whether this was cowardice or that

he was strongly advised by the ruling Covenanters to save himself – he was

no use to them if dead. But it is quite likely that the common people of

Argyll felt abandoned by his action and chose not to resist the plundering

forces of Montrose.

Inverlochy February 2,

1645

The army went then to

Lochaber where they were joined by an advance party of the MacLeans under

their chieftain Sir Lachlan MacLean of Dowart in the Isle of Mull and

about 30 soldiers. Going to Glengarry where more joined them, Montrose

learnt that Argyll and his cousin, Sir Duncan Campbell of Auchinbrack, who

had been recalled from Ireland, were at Inverlochy.

The 3000 Campbells gathered at Inverlochy were

confident that they were safe in their remote lands in winter especially,

but that did not deter Montrose. Rather than fight the force assembled at the head of the Great Glen that prevented his escape, he cleverly decided to use his force`s ancient animosity to the Campbells as a tactical weapon. He marched his army through the Glen of Albin, along the rugged river valley of the Tarf, over Lochaber mountains

and round the edge of Ben Nevis to do battle on Sunday, February 2, 1645.

At Inverlochy on the

Saturday evening, Argyll again set himself aside

from his troops, taking to a barge on Loch Linn from where he dictated his

battle orders. Argyll’s forces opened fire on the Royalists with cannon

and muskets shortly after sunrise but again after the first exchange of

muskets the Irish troops advanced and took Argyll’s standard and the

standard bearer. The loss of the

standard was followed by the army breaking up and there followed a hot

pursuit for over nine miles in which hundreds of the Campbell men were

slaughtered. Auchinbrack was killed, beheaded – helmet and all, by one

sweep of Alexander McColl’s claymore, with 16 or 17 other Campbell chiefs

and some lowland chieftains; 4 more Campbells were taken prisoner at

Bearbrick on Loch Awe. In all some 40

ranking Campbells were killed and 22 lowland chieftains released on giving

their oath not to bear arms again; and 1700 of Argyll’s troops were also

killed. This battle destroyed the Campbell clan`s military reputation and convinced George, 2nd Earl of Seaforth to disband his his cavalry.

Dundee March 1645

Towards the end of March,

1645, Montrose was pursuing the Covenanter General Hurry across the River

Esk to Dundee, a town that had previously resisted Montrose. Blocked from going south by Lieutenant General William Baillie, Montrose decided to satisfy his troops desire for plunder by loosing them on Dundee. The city was

attacked by Alastair McColl and his Antrim soldiers along with troops and cavalry led

by Lord George Gordon, a younger son of the Marquis of Huntly.

A formal surrender was

being concluded when a message was received that Generals Baillie and

Hurry with 3000 Covenanting foot soldiers and 800 cavalry were just

outside the city. Montrose retired very quickly to Arbroath with his small

force of about 700. The Covenanting

generals rested the night at Forfar, thinking that they had Montrose

bottled up, and planned to deal with him the following morning. But during

the night Montrose daringly took his army past the Covenanters and escaped

via Kerriemuir to South Esk. Learning that more of his troops had escaped, he made a forced march of three days and two nights to escape into the

Grampian mountains.

Auldearn May 9, 1645

The next conflict was on

May 9, 1645, at the village of Auldearn near Nairn. On this occasion

Montrose’s forces were outnumbered by the army of Sir John Hurry assisted

by George MacKenzie, the Second Earl of Seaforth; John the thirteenth Earl

of Sutherland; and James Ogilvy First Earl of Findlater. With a motley army of about 4,000 men, Hurry attempted a surprise attack on Montrose; but musket firing by the Covenanters to clear potentially damp powder from their muskets, alerted the royalists. The immediate response came from MacColl and his Irishmen who stayed the Covenanter attack while the rest of Montroses` force were organised for a counter attack.

In this battle the royal

standard was entrusted to Alastair McColl and his Irishmen. Montrose could

only allow about 400 troops for the defence of the Standard and instructed

McColl to stay within the trenches where they were placed. But in the heat

of battle the Irishman could not resist a dash at the enemy and he and his

band were instantly surrounded. It required a supreme effort to fight

their way back to the trenches. While

holding the rearguard McColl broke his sword and his brother-in-law

Davidson of Ardnacross, handed him his during which Davidson was mortally

wounded. For his impetuosity McColl had 17 of his officers and veterans

wounded but the royal standard was safe. The MacDonalds and the Gordons

performed especially well and at the end of the day over 2000 Covenanters

lay dead.

Alford July 2, 1645

On leaving Auldearn

Montrose marched rapidly into Aberdeenshire to overtake a Covenanter army of about 2,000 men

under under General Baillie (Baillie of Letham) and Alexander Lindsay, the

Earl of Balcarres. This he did at Alford on the River Don where his 1500 warriors took on the Covenanters – after the

battle some 700 Covenanters lay dead on the field. Montrose suffered

losses too, including Lord Gordon of Aboyne, the eldest son of the Marquis

of Huntley. General Baillie meanwhile withdrew and made his way to Perth

pursued by Montrose`s forces. For all practical purposes Montrose had now eliminated any serious opposition north of the river Tay.

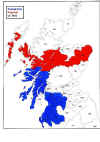

Kilsyth 15 August 1645

Thinking that Montrose

might be making for Edinburgh, General Baillie and Argyll formed another

army of some 7000 foot soldiers and 1000 cavalry which was assembled at

the village of Kilsyth. Alexander McColl was again an important factor,

this time by keeping the impetuous Clans in control who were squabbling

over precedence in the battle. This concerned 700 Macleans and 500

Clanranald who had not fought at Alford, but who wanted honours like the

Glengarry had gained previously.

On August 15, 1645, yet

again Montrose was victorious, this time pursuing the fleeing Covenanters

for 14 miles and leaving 3000 dead in his wake. Argyll this time fled to

Queensferry where he took a boat to Newcastle. Many of the other

Covenanter leaders took refuge in Stirling Castle.

Philliphaugh September 13, 1645

Moving on to Glasgow,

Montrose and his army were met by a remarkably friendly populace and he

sent McColl into Ayrshire, the Covenanter heartland, to negotiate terms

with the landowners particularly. The fearsome reputation of the Irish was alone enough to disperse the Covenanter levies. This

was in the last two weeks of August, during which time most of the

Scottish clansmen had returned to their homes with their booty; the

Gordons too had returned to the north east. McColl meanwhile had left between 5-700

of his infantry with Montrose. Thus

reduced in number the denuded forces of Montrose, now only numbering about 2,000 in total, were relaxed and unprepared when David

Leslie and the Covenanter forces surprised them at Philliphaugh, near Selkirk, on

September 13, 1645.

Leslie, the nephew of Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven, had forced march from the siege of Hereford which he left with about 4,500-5,000 horse on 12 August. By the 14th he was in Stourbridge, 15th at Uttoxeter, 16th at Ollerton where he linked up with some 1600 horse under Sir John Gell. On the 21st he rendezvoused on Doncaster Moor picking up more troops. He reached Berwick on 6 September, via Newcastle, and Selkirk on the early morning of the 13th September. Montrose compounded his defeat by not preparing defences and many officers took themselves off to comfortable quarters at Selkirk. The lack of proper sentries and absence of their officers left the troops at the mercy of Leslie.

This time the Royalist

forces were massacred with over 500 of the Irishmen cut to ribbons after

they had been offered quarter and had surrendered. There followed a

slaughter of the camp followers – boys, cooks and women. Three hundred

Irish women, wives of the soldiers, and many pregnant were cut up –

literally, and unborn babies cut from the womb and cast on the ground with

their murdered mothers. The horror of

this was compounded by Covenanter ministers who incited all and any

retribution on the royalists.

In the period after

Philliphaugh and December 1, many of the Scottish nobility who had taken

part were rounded up. Any Irish found or held in prison were summarily

executed by order of the Estates (the Scottish Parliament) who directed :

“This House ordains

the Irish prisoners taken at and after Philliphaugh in all the prisons of

the kingdom, especially in the prisons of Selkirk, Jedburgh, Glasgow,

Dumbarton and Perth, to be executed without any assize or process… “

Montrose managed to gather some more forces but wasted them in a siege of Inverness. The Gordons again took the field but neither party were able to mount a serious threat to the Covenanters. The last serious confrontation occurred in October 1645 when Lord Digby and Sir Marmaduke Langdale with the Northern Horse, invaded Scotland to assist Montrose. Learning of this, Covenanter forces under Colonel Sir John Browne marched from Carlisle with eight troops of horse. At Annan Moor in Dumfriesshire the Northern Horse were routed and its officers fled to the Isle of Man. Leslie meanwhile left Major General John Middleton (the same man responsible for later persecution of the Presbyterians following the Restoration of Charles II in 1660) to contain the royalists while he returned to England to make an important contribution to the siege of Newark; and the surrender of Charles I to the Scots on 5 May 1646.

The end of James Graham, Marquis of Montrose.

Bonar Bridge April 27,

1650

Montrose escaped from the

disaster at Philliphaugh into the Highlands where an attempt to recover the royalist cause was made, but from there he went to

Holland and Norway. Still loyal to his king, now Charles II (who was

double dealing and negotiating with the Covenanters even while Montrose

fought) he had one a last gamble landing in the Orkneys in March 1650 with

1200 continental mercenaries.

Unfortunately for Montrose,

he could gather little help and met with the Covenanter forces under

Colonel Strachan at Carbisdale near Bonar Bridge on April 27, 1650.

Here the Royalist fortunes took a severe battering with some 500 killed,

200 drowned and 250 captured. Montrose himself was seized a week later by

Neil Macleod of Assynt at Ardvreck Castle.

Time was short for Montrose, as he had

already been convicted and sentenced in 1644. There was no trial and he

was sent to Edinburgh for execution. Come the day of execution, May 21,

1650, it is recorded that he was resplendently dressed in rich scarlet,

overlaid with silver lace, white gloves and silken stockings as if going

to a wedding. He

was hung in the Grassmarket, Edinburgh. After he was dead his head was

severed, as was the custom for alleged traitors, and placed on a spike at

the Tolbooth and his other limbs were distributed to the four major cities

of Scotland for display in places of prominence. Montrose’s remains stayed

exposed for 11 years until he was finally laid to rest in St. Giles’s Kirk

at the Restoration of Charles II in 1660.

Postscript.

Some historians tend to

understate the contribution of the Irish troops supplied by the Earl of

Antrim. They were not by any means the untrained local militia drummed up for

service, or wild hairy men from out of the bogs, but seasoned full-time

soldiers who had been fighting in Flanders. Moreover, with good officers and a proper

command structure they were well disciplined in battle; they had developed

their own novel tactics which proved very successful, and they were led by

a charismatic as well as brave leader in Alastair McColl.

Today we might compare them

as akin to Commandos or Rangers who lived off the land, travelled quickly

often over rough terrain and who struck decisively at their objective

before moving on to the next task. The opportunity to take revenge on

their ancient enemy the Campbells was undoubtedly the governing factor and

also their weakness, much preferring to gain revenge on their old enemy

than fight for a foreign king who cared little for them.

|